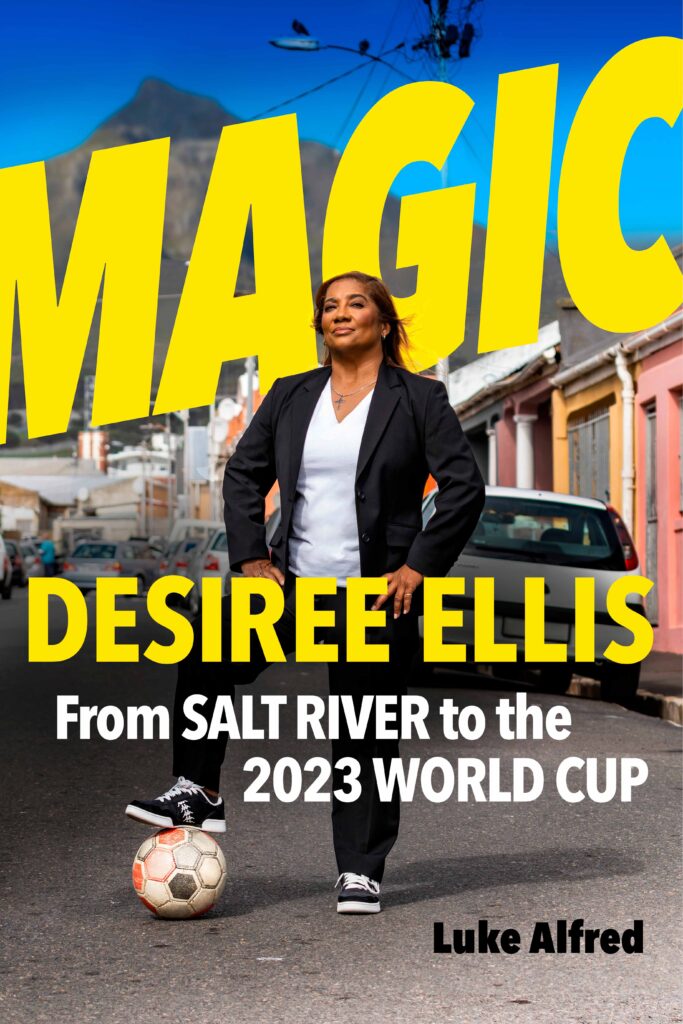

Leadership is delighted to publish an extract from Luke Alfred’s book, ‘MAGIC: Desiree Ellis–From Salt River to the 2023 World Cup’

Desiree enjoyed life on the streets of Salt River and her high energy levels and natural exuberance found an immediate outlet in street soccer. She wasn’t one to play with dolls and never liked wearing dresses, once complaining to Ernest after Natalie bought her a swanky dress as a teenager that she would never wear it. Instead she retreated somewhere dark and private to have a good cry.

She played with boys—and girls—but mostly boys because her cousins were boys and boys were good at things she liked doing and was herself good at, as in those days not many girls played predominantly ‘boys’ sports’. Ball games were played outside to the constant sound of the trains that clattered up or down the nearby railway line. She loved the vitality of street life, the smell of Table Bay and the docks, and the muzzle of fog, which often flooded into Salt River as summer cooled through autumn and into winter; she loved the noises of the streets, the dogs, the shouting, the endless passing parade, people calling to one another, the shouting and the vloeking. Being cooped up indoors was boring by contrast.

In 1970, Desiree started school. This was Dryden Street Primary, which was close to Auntie Susan’s house on Greef Street. To get there the children had to cross the much busier Albert Road, though, so they crossed carefully, holding hands, when they were either going to school or returning home for the afternoon.

Although she was a clever child, and with an annual R400 school bursary to help her and the family, her mind was on sport and soccer, so for Desiree school was a chore to be endured, and this she did with her customary perky equanimity. What she really looked forward to while growing up was what happened after school and she was free to roam the streets and do her own thing with her sisters, cousins and schoolmates.

For Desiree the streets meant freedom. Sometimes she and her sisters and cousins would go to Salt River Station to watch the trains as they either moved up the line to Cape Town’s central station or sped down towards Mowbray and Rondebosch and stations beyond that. They would play in the green space abutted by Westminster Road, just a kink of the road away from Greef Street where Susan lived.

Desiree tried her hand at cricket and even rugby, although rugby was played with a strange-shaped ball that bounced wildly and unpredictably. She wasn’t sure if she liked that very much. A sport where the bounce of the ball couldn’t be trusted was a sport that couldn’t be trusted. She also tried netball. It was thought of as girls’ stuff and you stood still at least some of the time.

At Natalie’s insistence she even tried ballet. As an eight or nine-year-old, she and her sisters Carmelita and Erna were bundled off to the newly built Joseph Stone Auditorium in Athlone, where the Eoan School of Performing Arts had their headquarters. Natalie liked her daughters to be more ladylike. Ballet was part of her image of what young women should be.

Desiree’s image of herself wasn’t quite like that. She gave ballet a try but when it reached the stage where little wooden blocks were placed in the ballet shoes to help the girls to stand on tiptoes, she, well, put her foot down. Standing on tip-toes was silly. And painful. Who stood on tip-toes anyway? The sports she knew didn’t require any standing on tip-toes. The only time she could think of needing tip-toes was when she was reaching up to look for something on top of one of her cupboards. Desiree could be headstrong when she put her mind to something. After that, under no circumstances could she be persuaded back to ballet. It was over. She was off to Salt River High and that was just that.

Ballet paled beside the breathless, sweaty excitement of street soccer, the thunder on the tar. She and her mates, a dynamic group that sometimes involved her cousins, sometimes not, played endless matches of street soccer on the roads between Albert Road and Salt River Station, Westminster Road, Portland Road and Foundry Road.

Matches were patiently waited for and keenly contested. Mixed teams of both boys and girls bought T-shirts at Pep Stores in red, white and blue to distinguish them from their opponents. The matches went on for hours. Desiree remembers that Westminster used to join Foundry at right angles and that one of the ‘courts’ on which street soccer was played provided a wall off which you could play canny one-twos to get round your opponents. It was the greatest fun, better than sitting in a classroom, and, so, so much better than ballet.

Small like her mother, Desiree had a big heart and was difficult to intimidate. She was feisty and could run for years. The main problem for her and her sisters wasn’t the condition of the ball, the strength of their opponents or the fact that her homework might not have been finished before they rushed out of Auntie Susan’s house to play – homework was an issue better left for another day.

No, the biggest concern of all was footwear. The Ellises could not afford takkies or trainers for their daughters, and boots at this stage of their development were unheard of. Desiree played street soccer in her school shoes, Bata Toughees, and although Toughees were meant to be the most durable and, well, toughest, school shoes on the block, they took a fearful pounding week after week in the hard school of knocks that was street soccer.

There was only so much money to go around in the Ellis family. Normally a gentle and even-tempered man, Ernest showed signs of bother when it came to inspecting Desiree’s and his other daughters’ Toughees. Tough they might have been but they were meant to last and they were somehow never quite tough enough. Desiree remembers that Ernest would actually take off her school shoes when he picked her and her sisters up from Auntie Susan’s place after work to prevent further wear and tear. Each daughter was meant to see to it that a pair of shoes lasted the entire school year.

Street soccer wasn’t the only way to while away the long afternoon hours—although it was probably the most enjoyable. The suburb was a safe one in which to wander. Desiree was once found on the platform of the Salt River Station holding the hand of a little boy as they considered how far they might be able to get without train fare. It was all innocent fun but the boy’s mother was not best pleased when she eventually found her son. Boarding a train on the fly wasn’t something Desiree tried again soon.

Desiree found as she was getting slightly older that she was fascinated by what was in Auntie Susan’s pantry. Every so often she would raid the pantry, not for her own use, but because she thought there were more deserving folk walking down Greef Street. Not wanting them to go hungry, she would throw cans of food and packets of rice over Auntie Susan’s fence so they could be picked up by pedestrians walking down the road.

Desiree has always had a slightly odd attitude to money and possessions. At least some of what she has she gives away. This is something she has always done. Her mother Natalie says her eldest daughter was peculiar about money from an early age. The children were given pocket money but it wasn’t much and it wasn’t regular. It was based more on the principle that when the family had money, the children were given a small stipend, which fluctuated depending on the family’s finances at the time. As the eldest, Desiree was given more than her sisters and brother, but, unlike them, she wouldn’t spend what she was given.

Sometimes Natalie would need to find an item of school clothing, for example, something to wash or mend, and would look for it in Desiree’s chaotic cupboard. There she’d find rolled up wads of money. Desiree didn’t spend money on fripperies like lucky packets, movie tickets and sweets. Rather she saved for truly big items, things she really liked, a brand-new jumper, for instance, or a new pair of boots. In later life she always gave some of her money away to charities, NGOs and just causes.

Luke Alfred is the author of ‘MAGIC: Desiree Ellis–From Salt River to the 2023 World Cup’.