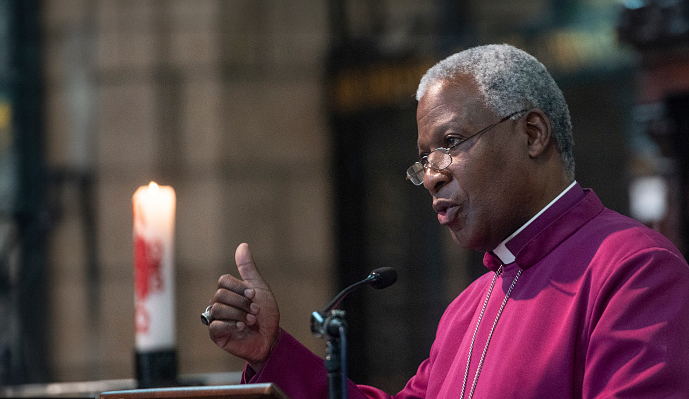

This is an extract from the Midnight Christmas Message by Dr Thabo Makgoba, the Archbishop of Cape Town, at St Georges Cathedral in Cape Town last year

The state of our nation and the state of our world render us a confused human race. Our time feels more like Passion Week, in which we are anticipating a death, even though we know that that is followed by the power of the Resurrection.

Last year, a pro-Palestine protest in East London touched my heart deeply, for a banner carried by marchers drew vivid attention to the many thousands of children reported to have died in the war in Gaza: Each one of those children, the banner said, had names and they had dreams. Tonight it is not even possible to think of Christmas, Bethlehem or the baby lying in a manger without hearing the haunting cries, the desperate wailing of babies, not in mangers but under the rubble, in the shells of bombed hospitals, 70 kilometres away from Bethlehem in Gaza. For 80 days the crying has not stopped. More children have died in just over two months in Gaza than in the all the conflicts around the world over the past two years. That is staggering.

Indeed, even on the West Bank, around the very place where Jesus was born, more than 400 people have been killed by settlers and the Israeli Defence Force in this year alone. It is all so reminiscent of the Biblical record in Matthew (2:18):

‘A voice was heard in Ramah, wailing and loud lamentation, Rachel weeping for her children; she refused to be consoled, because they are no more.’

Too many children are no more in the place where Jesus was born, in the land in which he lived and ministered, and the territories through which he journeyed. The parallels between the time of Jesus’ birth and the cruel reality in the Holy Land today are obvious. We have to face the fact that even as military operations continue in Gaza, vulnerable people are forced to move from one place to another, no place seemingly safer than the last despite the protestations of the Israeli military. The United Nations reports that that 1.4 million people have been driven from their homes and now the entire population of about 2.2 million people is suffering crisis or worse levels of food insecurity. We see today a tragic replay of the bitter politics of disruption of two thousand years ago, the same disruption by the powerful, by an occupying force, that displaced Mary and Joseph at the time of Jesus’ birth and forced them to move from Nazareth to Bethlehem.

Three months ago, would we have believed it if anyone had told us that nearly 25 000 people—more than 20 000 Palestinians but also Israelis—would be dead by Christmas? The American senator, Bernie Sanders, put this in historical perspective this week when he told the US Congress that the destruction in Gaza was now equivalent to that of the German city of Dresden, where, notoriously, two years of bombing during World War II destroyed half of the homes and killed about 25 000 people. Gaza, he said, has matched this in two months.

Seventy-five years on, the world is supposed to have become a better place in its abhorrence of war. Under the international humanitarian law which has been developed since then, it is said that Winston Churchill would now be deemed a war criminal for the bombing of Dresden. But in the Holy Land, it is as if the military wings of Hamas and Israel have reverted to fighting by the standards of atrocity deployed three-quarters of a century ago. Both sides now stand condemned for breaches of international law in this horrible war. There is little doubt that adherents of both sides, in both Gaza and the West Bank, have committed war crimes. There are leaders on both sides, of Hamas and Israel, who have made declarations and statements which either constitute incitement to genocide or will be interpreted as such by their followers.

I have been asked what message our church was sending a few weeks ago when we allowed Hamas leaders to join a vigil here in the Cathedral. My reply has been simple, reflecting the words of Desmond Tutu inscribed on one of the windows of the Link at the back of this church: “If you want peace, you don’t talk to your friends. You talk to your enemies.” In his case, when the PW Botha government was behaving as an enemy to our people, Archbishop Desmond nevertheless repeatedly talked to Botha. And when he met Botha, he urged him to negotiate with those his government deemed “terrorists” who needed to be “eliminated”. In the 1990s, he urged Madiba to talk to Prince Buthelezi when the ANC in KwaZulu-Natal rejected dialogue on the grounds that the IFP was killing women and children, trying to shoot its way to power. And in Ireland, he angered the British government in 1991 by urging them to talk to the IRA, whom they then regarded as terrorists.

The attitude of many Western countries in their almost unconditional support of Israel, designating Hamas as a terrorist organisation, beyond the pale, is very worrying in its implications. For what will they and Israel do if Palestinians, when finally able to vote in a free and fair election, choose Hamas to represent them?

Let me end this reflection on Palestine by simply stating: This war must stop. Prime Minister Netanyahu and Hamas leaders must go to the table. The Americans must stop arming Israel, Iran must stop arming Hamas, and anyone else supplying weapons to those killing fields must stop doing so. Neither soldiers nor civilians are machines, cannon fodder to be used for other people’s ends. Arms never win peace, no matter who the enemy is—they only enrich the arms manufacturers and their shareholders, whose shares on the stock exchanges of the world will go up and up.

On this holy night, it is not only Gaza which is engufled in war. Our world is sick with war, in 40 different places on a recent count. The disruption which characterised the Holy Land at the time of Jesus’ birth, and which we see again today, is replicated in Sudan, where the United Nations tells us that nearly six million people have been forced from their homes. Since two heavily-armed military forces began a civil war nine months ago, more than 9 000 have been killed, and the fighting has helped to drive more than 17 million people into high levels of acute food insecurity. Just this week, fighting south and east of Khartoum forced the UN’s World Food Programme to suspend deliveries to a state where it was regularly feeding more than three-quarters of a million people. In the face of this horrifying humanitarian catastrophe, the world has been scandalously silent.

At home here in South Africa, the cries of Rachel weeping for her children also sound from the streets around us, the cries of those terrorised by gangs whose violence disrupts whole neighbourhoods of our cities and destroys the social fabric stitched together by those who have longed for peace. The cries of the survivors of gender-based violence and the deaths of those killed by intimate partners is a scourge which scars our society. There are far too many Rachels, both in our midst and thousands of kilometres from us, who cry out to heaven.

Eight years ago, when we marched in a Walk of Witness to Parliament here in Cape Town, I deplored the lack of trust between political leaders and the people of our country. In my speech, I asked: “Doesn’t the distrust we feel in today’s leaders feel more or less like the distrust we felt during the days of apartheid?” Last week, I was deeply disturbed to read the results of a new survey by the Institute of Justice and Reconciliation showing that decline in people’s trust. In 2013, two out of every 10 South Africans said they found it difficult to trust that our leaders would do the right thing. A decade later, the figure has quadrupled—in 2023 eight out of every 10 people agree that leaders are untrustworthy.

So now let us finally admit to one of the saddest lessons of history: if you have been lied to long enough, you tend to ignore any evidence of the lies, no matter how negatively they impact our lives day in and day out. It is frightening to realise that as a society we’ve become so worn down by lies, corruption, and incompetence that we’re no longer interested in finding out the truth. We’ve been captured by lies. Meanwhile, as politicians begin to realise they may not be in power after the next election, their deception, scams and fraud grow more blatant by the day as they grow hungrier and hungrier for the ill-gotten proceeds of power. They walk shamelessly and brazenly with their dirty feet through every aspect of our South African lives. Adding to this crisis is the revelation in the Medium-Term Budget Policy Statement that 55 000 public servants now earn more than a million rand a year. Fifty-five thousand! This when eight-and-a-half million desperate people receive a social grant of R350 a month!

The political class, including the socialists among them, get bigger and bigger. They produce nothing, create nothing, and maintain very little, if anything. Everything they touch seems to fall apart, while they consume more and more and the entrepreneurial class gets smaller and the number of listed companies shrinks every year. The working class faces a tougher environment with less growth and fewer jobs as politicians leech the economy and stay in power basically by drugging the working class, making them believe they’re getting all this free stuff. But at the end of the day, everyone, including the poor, pays for it through higher inflation and other economic ailments.

Nevertheless, this Christmas we must refuse to be overwhelmed by despair. At a time when it is almost impossible to imagine an end to war, an end to the lack of respect for women and children in many homes, an end to the tyranny of gangsterism, and an end to corruption and misrule, we must look again at the manger. For the truth of Christmas is that our Saviour came to bring us hope, light, and the determination to refuse to give in to darkness, and he did this in the most marginal of places, amidst displaced parents far from the centres of power, in a time of occupation and resistance. It is there, amongst those the world judges as being of no account, that hope is born.

Christmas is the feast that underlines that no one is excluded from places of blessing, from spiritual growth and inspiration. Around the manger no one is excluded, no one is unworthy. Every barrier dissolves. There is no place for distinction, discrimination or injustice. All are welcome across class, race, sexual orientation, migration status, religion, and every other divisive distinction. The manger is really a home for all. In a world of exclusion and of demonising others, the manger is a radical alternative, a new narrative across the old practices of elitism and self-righteousness.

Even with the challenges the world faces in the Holy Land, Sudan, and other places of conflict, and in our own communities, the Christmas hope for peace and goodwill toward all cannot be dismissed as a pious dream. That baby has a name and his Creator has a vision for the world through his life: not to destroy and maim, nor to misuse the instruments of power for our own ends. If we are to have peace in the world, we must all embrace the affirmation that ends and means must cohere. There have always been those who argued that the end justifies the means, but we will never have peace or harmony in the world until everyone everywhere recognises that ends are not severed from means. Ultimately, you can’t reach good ends through evil means, because means represent the seed, and the ends represent the tree.

The Christmas story and message is: Don’t fear standing up to those who make war; don’t fear those who abuse power, whether in public life or our neighbourhoods and homes. Have hope, because we have overcome in the past and we will overcome in the future. No matter how awful and brutal the world, as we put up our hands this Christmas because we have touched hope in some places, we realise again that we are not alone. The great truth is: Emmanuel! God with us! Nkosinathi! Like the shepherds, let us leave this Cathedral Church tonight praising God for in the midst of all that is happening “A child has been born to us…” and that makes all the difference.

Dr Thabo Makgoba is the Archbishop of Cape Town.